The Last Picnic (2025)

Scroll (in custom-made box)

Open: 28cm x 178cm (11″ x 70″)

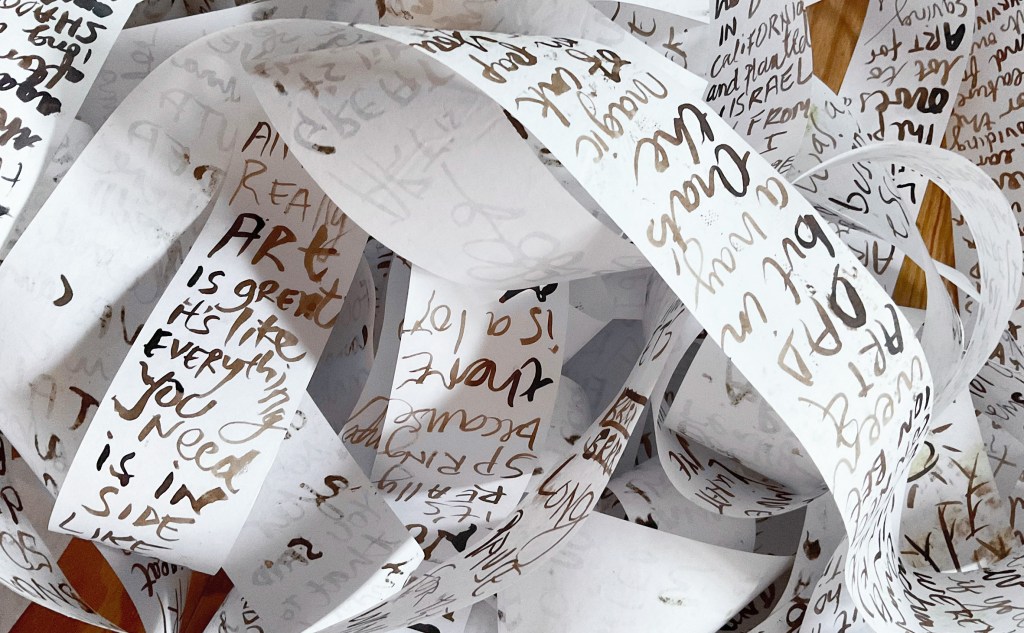

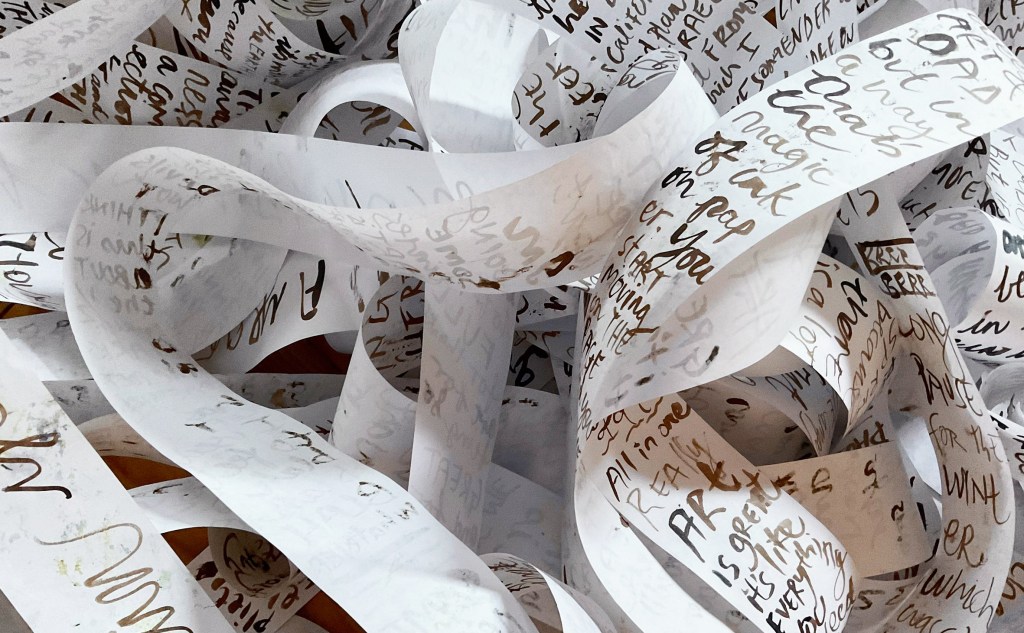

Materials Marker Pens on 250gsm paper, flip top box

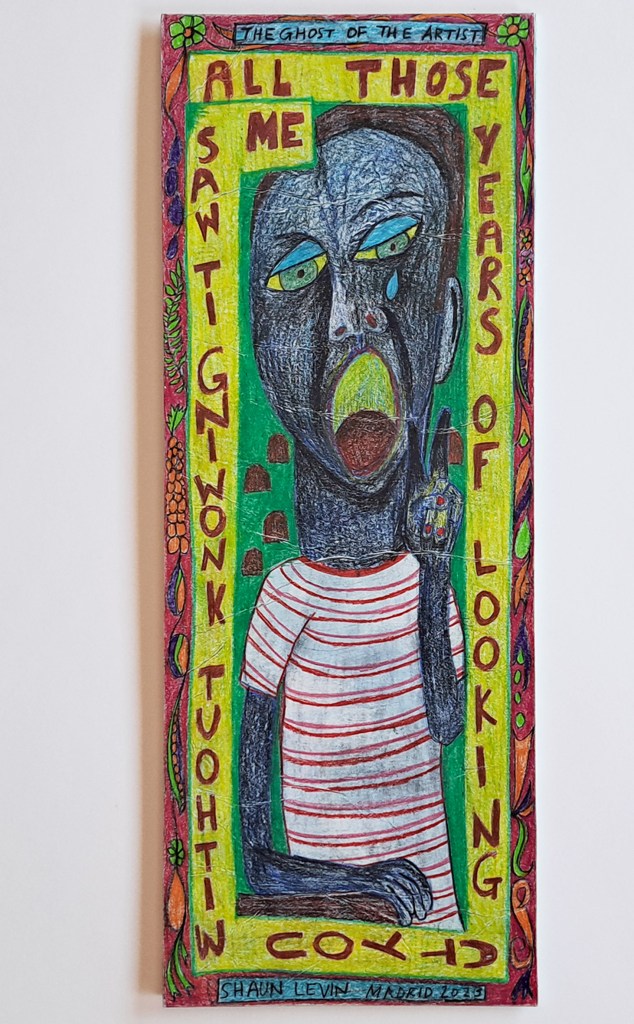

The Last Picnic is a scroll created in response to the ongoing destruction in Gaza and the religious-nationalist fervour in Israel that underpins it. The scroll opens to reveal a single continuous drawing in black marker on yellowed paper (an earlier drawing forgotten): a picnic table in red, surrounded by figures caught in a moment of fractured communion. The composition echoes Da Vinci’s Last Supper, a gathering teetering on the edge of collapse. Some figures stare directly outward, others are lost in phones, in drugs, in grief, rage, or comfort. Relics of violence – an abandoned doll, a drone, a pair of shoes – scatter across the tablecloth.

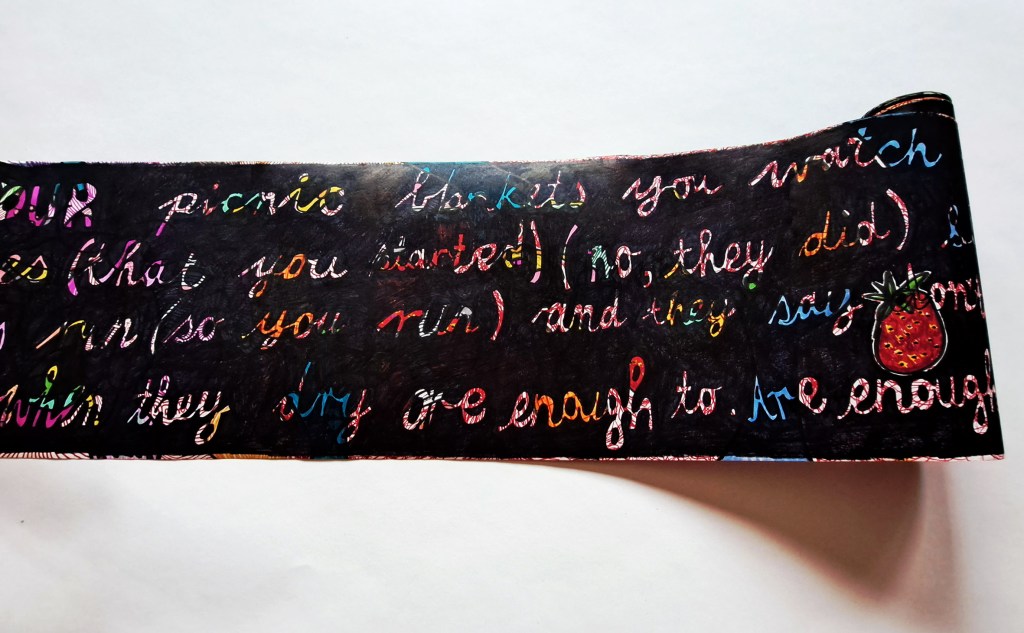

On the reverse of the scroll is a handwritten text, formed in multicoloured cursive over a dark surface: From your picnic blankets you watch the city in flames and the fires (that you started) (no, they did) slowly make their way to you someone says run (so you run) and they say don’t look back (but you look back) and the tears when they dry are enough to. Are enough enough enough.

This text overlays what was once a colourful drawing of a picnic: people kissing, fruit, a shared blanket. That earlier image has been erased, charred over, though faint traces remain. The colour beneath is both ache and hope: a suggestion that no people, no joys, can be fully erased.

The scroll connects to the Torah scrolls and Dead Sea Scrolls of my time in Israel-Palestine, of growing up in a Small Jewish community in South Africa, and to the long tradition of stories that spread out across time and generations. Having lived in Israel for nearly twenty years, served in the Israeli military, and left in the mid-1990s, I’ve watched with sadness and horror as the country has moved ever further to the right. The current onslaught on Gaza feels not only catastrophic but Biblical in tone, waged by a government driven by Messianic beliefs and a literal reading of scripture.

The title refers to a moment on the edge: a final joy before collapse. The last picnic in Gaza before the bombs fell. The last picnic in Israel before the attacks in October 2023. The drawing references images of Israelis gathering on hilltops to watch the bombardment of Gaza, like some grotesque cinematic event. I want The Last Picnic to live in all the complexity of witnessing, betrayal, participation, and denial.

Much of the scroll is in black ink: a deliberate flattening of nuance, a reflection of how the world is increasingly seen in absolutes. But even through the layers of erasure, colour insists on its presence. It is not the optimism of recovery, but a kind of visual resistance: the past refusing to be fully covered over.

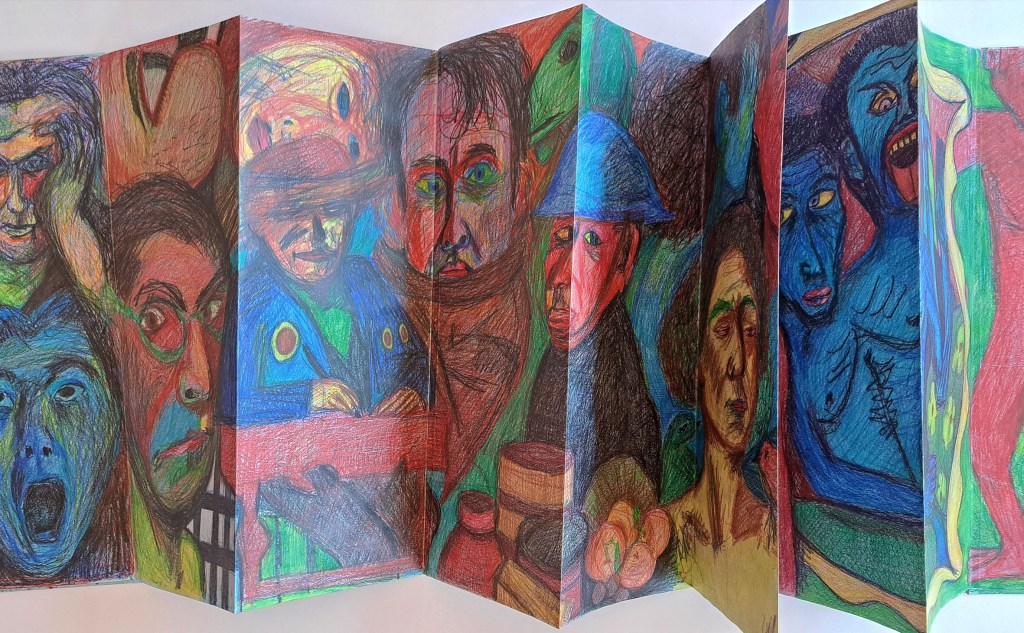

My recent artists’ books – scrolls and concertinas – are becoming more compact to hold but larger when unfolded. I want them to be portable and vast, intimate and immersive. The Last Picnic is stored in a custom-made flip-top box, a kind of reliquary, inviting the viewer to peer inside, to participate, to bear witness.

You must be logged in to post a comment.